Slop Guard: Prose Linter for AI-Assisted Writing

AI-generated text falls into patterns. Not errors, but habits: “delve” instead of “dig,” three-beat cadences on every list, bold headers followed by explanation paragraphs, the same sentence structure repeated ten times in a row. Any one of these is fine. A human writer might use any of them. The problem is density and repetition. When the same handful of constructions dominate 500 words of prose, the writing feels flat and formulaic.

I work with an AI coding agent for most of my development. That agent also writes prose: blog drafts, PR descriptions, documentation, technical explanations. The prose is competent. It’s also formulaic in ways that make it unpleasant to read. I wanted a tool that would catch those patterns and push the output toward better writing.

The obvious approach is to use an LLM as a judge. Feed it the text, ask it to score. This works, but it’s slow (an API call per check), expensive (token costs on every draft), non-deterministic (different scores on the same text), and a little circular (using the thing that produces the slop to judge the slop). I wanted something faster and more mechanical: a linter rather than a critic.

Prior Art

The idea of cataloging these patterns isn’t new. A few existing resources informed this work.

@secemp9’s anti-slop rubric is a structured XML prompt that scores text 0-15 across five criteria: neutrality and tone, formulaic scaffolding, meta-communication, markup artifacts, and watermarks. It’s designed as an LLM judge prompt, but the criteria are a useful catalog of what to avoid. The word lists and structural patterns in the rubric directly informed my implementation.

EQ-Bench’s slop score provides frequency data: “delves” shows a 25x increase in usage post-2023, “showcasing” and “underscores” around 9x. The words that spiked are almost universally vague replacements for more specific ones.

Wikipedia’s “Signs of AI Writing” is a community-maintained guide with 26 rules cataloging formulaic patterns, from superficial analysis to repetitive transitions. And llm-cliches provides curated word lists organized by part of speech.

These resources identify the patterns. What I wanted was a tool that could score them automatically, fast enough to run on every draft.

The V0 Implementation

The slop guard is a single Python file, runnable as an MCP server. Two tools: check_slop(text) returns a JSON score with violations, and check_slop_file(file_path) reads and scores a file. All regex is compiled at module level. No dependencies beyond the MCP library.

The rules span vocabulary, phrases, structure, tone, and rhythm.

The vocabulary list contains about 80 words statistically overrepresented in LLM output: adjectives (crucial, groundbreaking, seamless, robust), verbs (delve, leverage, harness, orchestrate), nouns (landscape, tapestry, paradigm, trajectory), and hedge words (notably, moreover, furthermore). Each hit costs 2 points.

The phrase list contains about 50 patterns characteristic of assistant-mode output: “it’s worth noting,” “let’s dive in,” “not just X, but Y,” “you might be wondering.” This includes meta-communication (“would you like me to”), restatement transitions (“in other words,” “the key takeaway”), and menu-of-options offers (“if you want, I can”). Each costs 3 points.

Structural rules catch the shape of AI writing. The bold-header-explanation pattern (**Bold claim.** Explanation paragraph. repeated three or more times), runs of six or more consecutive bullets, triadic constructions (“X, Y, and Z”). These are structural patterns, independent of vocabulary.

Tone rules catch false narrativity (“then something interesting happened”), sentence openers that telegraph agreement (“certainly!”, “absolutely,”), and weasel phrases (“many believe,” “studies show”) that assert authority without citation.

Two more specialized rules round out the set. A rhythm detector measures sentence length variance as coefficient of variation; when CV drops below 0.3 across five or more sentences, the text has the metronomic cadence of LLM output. Human writing has jagged rhythm: short sentences after long ones, fragments after compounds. And an em dash density check flags anything over one per 150 words.

The scoring started simple: 100 minus the sum of penalties, clipped to 0. Anything above 80 was “clean,” below 40 was “heavy.” Fast to implement, easy to understand. And, as it turned out, almost completely useless at catching the patterns that actually make edited AI prose feel flat.

Where V0 Failed

I wrote a blog post with the agent’s help. The post covered BM25 search for agent memory. Before publishing, I ran it through the slop guard. Score: 100. Perfect. No violations detected.

Then @xeophon read it and noticed the prose was repetitive in specific ways. The patterns he flagged:

- “Useful, but incremental.” A pithy evaluative fragment. Short sentence, comma, pivot word.

- “keywords, not questions” and “terms, not questions.” The “X, not Y” contrast pair, a construction that gets monotonous fast when repeated.

- Colon-elaboration patterns throughout.

These are syntactic patterns. The V0 linter was looking for bad words and bad phrases. “Keywords, not questions” is a perfectly natural English phrase. But three of them in 500 words becomes monotonous.

Calibrating Against Humans

The fix required two things: new detection rules for the syntactic patterns the detector was missing, and a scoring model that could distinguish “a human used this construction once” from “an LLM used this construction five times.”

For calibration baselines, I collected seven essays from well-known technical writers, all published before 2020 to avoid AI training data contamination:

- Paul Graham: “Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule” (2009), “Do Things That Don’t Scale” (2013)

- Dan Luu: “Sounds Easy” (2015)

- Richard Gabriel: “Worse is Better” (1989)

- Richard Hamming: “You and Your Research” (1986)

- Peter Norvig: “Teach Yourself Programming in 10 Years” (2001)

- Jeff Atwood: “The Best Code is No Code At All” (2007)

These represent different registers and decades. Any linter that flags Hamming’s 1986 lecture is broken. Any linter that gives formulaic Claude output a perfect score is also broken. The calibration target: the BM25 blog post should land around 50/100, and human text should land above 80.

New Rules

Two new categories targeting the repetitive constructions the linter was missing:

Contrast pairs. The “X, not Y” pattern, matched with \b(\w+), not (\w+)\b. Once is fine. Repeated use flattens the prose.

Pithy evaluative fragments. Short sentences (six words or fewer) containing a comma followed by a pivot word (but, yet, and, not, or). “Useful, but incremental.” “Simple, yet effective.” These are the compressed judgment patterns Claude defaults to when summarizing a point.

I also fixed the sentence splitter. The original regex split on [.!?] followed by whitespace, but it couldn’t handle closing quotes. The text "before?" Useful, but incremental. got parsed as one long sentence instead of two, so the pithy fragment detector never saw “Useful, but incremental” as a standalone short sentence. A small fix, but it was the difference between catching the exact pattern the collaborator flagged and missing it entirely.

The Concentration Multiplier

Here’s the insight that made the scoring work: what matters is whether violations cluster in the same category.

A text with three contrast pairs and two pithy fragments reads very differently from a text with one contrast pair, one slop word, one triadic, one em dash issue, and one hedge word. Same number of violations. Completely different signal. The first text has a monotone. The second is just imperfect prose.

The concentration multiplier applies to pattern-specific categories (contrast pairs, pithy fragments, and setup-resolution constructions). The weight for each violation scales with how many times that category appears:

multiplier = 1 + 2.5 * (category_count - 1)First occurrence: weight 1.0x. Second: 3.5x. Third: 6.0x. Three contrast pairs in one essay don’t get 3x the penalty of one. They get 6x, because the clustering is the signal.

Exponential Decay Scoring

The old scoring was additive: start at 100, subtract penalties. Everything clustered in the 90-100 range regardless of how bad the text was. The new scoring uses exponential decay:

score = 100 * exp(-0.04 * density)where density = weighted_sum / (word_count / 1000). The per-1000-words normalization means a 500-word text and a 3000-word text with the same violation rate get the same score. The exponential curve means a few violations barely register (a score of 95 instead of 100), but clustering drives the score down fast (50 at moderate density, 12 at heavy density).

Results

| Text | Words | Score | Band |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atwood (2007) | 1,302 | 91 | clean |

| Dan Luu (2015) | 2,141 | 88 | clean |

| Gabriel (1989) | 1,672 | 83 | clean |

| PG: Maker's Schedule (2009) | 1,183 | 82 | clean |

| PG: Don't Scale (2013) | 4,424 | 81 | clean |

| Norvig (2001) | 2,757 | 63 | light |

| Our BM25 Post | 1,839 | 45 | moderate |

| Hamming (1986) | 14,454 | 39 | heavy |

| Pure AI Slop | 1,261 | 12 | saturated |

Five of seven human baselines land in the “clean” band (81-91). Norvig at 63 (“light”) has three contrast pairs that fire the concentration amplifier. Hamming at 39 (“heavy”) is the interesting outlier: his 14,000-word lecture transcript accumulates natural speech patterns that the linter penalizes at scale. Five uses of “on the other hand” across 14k words is once every 2,800 words, completely normal in spoken English. But the density formula doesn’t distinguish between a 1,500-word blog post and a lecture transcript. The linter is calibrated for blog-length prose; longer texts will score lower even when the writing is fine.

The BM25 blog post, the one @xeophon flagged, lands at 45. The pure AI slop text (an unedited ChatGPT 5.2 blog post about AI agents) scores 12, driven by 40%+ bullet density, multiple bold-term bullet runs, blockquotes-as-thesis, and a menu-of-options offer at the end.

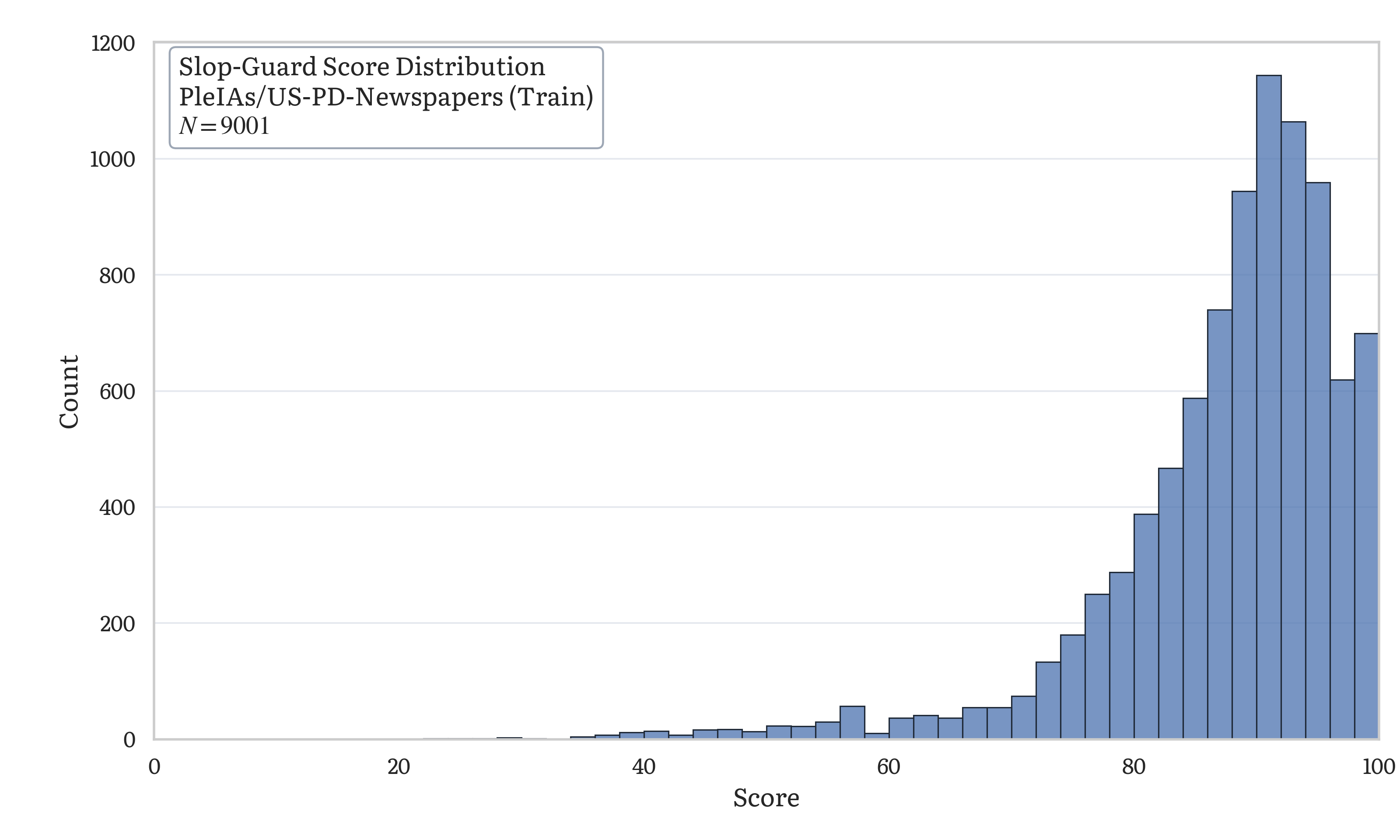

To check the scoring against a larger corpus, I ran the linter over 9,000 documents from PleIAs/US-PD-Newspapers, a collection of public domain American newspaper text. These are human-written, pre-internet, and predate LLMs by decades.

The distribution peaks in the 80-100 range, consistent with the per-essay calibration above. The long left tail comes from newspaper text that happens to use patterns the linter penalizes (formulaic transitions, repeated constructions) at higher density. Anything scoring below 50 is a clear outlier against this baseline and worth revising.

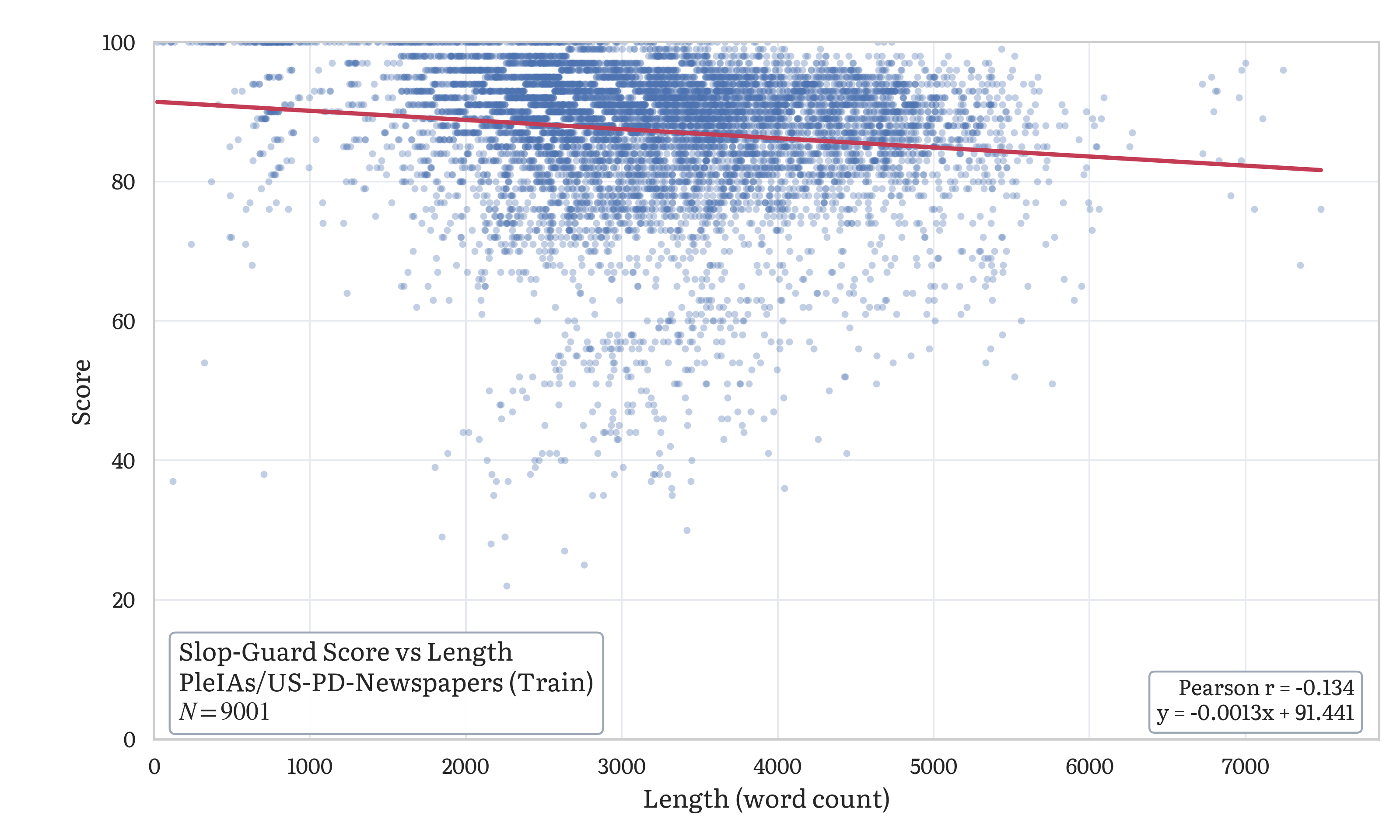

The weak negative correlation suggests the scoring isn’t trivially driven by length. Longer documents score slightly lower on average, but the effect is small relative to the variance in actual writing quality across the corpus.

Using It

The slop guard runs as an MCP server, which means any tool-using agent can call it as part of its workflow. In my setup, the agent checks its own output before presenting it: blog drafts, PR descriptions, documentation intended for other people. The check takes a few milliseconds on a typical blog post, and the response is structured for both the agent and the human reviewing its work:

{

"score": 0,

"band": "saturated",

"word_count": 49,

"violations": [

{

"type": "Violation",

"rule": "slop_word",

"match": "seamless",

"context": "The system orchestrates a seamless integration of cutting-ed...",

"penalty": -2

},

{

"type": "Violation",

"rule": "slop_word",

"match": "delve",

"context": "...raging robust frameworks to delve into the intricacies of th...",

"penalty": -2

},

{

"type": "Violation",

"rule": "setup_resolution",

"match": "It's not just a tool. It's",

"context": "...oblem landscape. It's not just a tool. It's a paradigm shift...",

"penalty": -3

}

],

"advice": [

"Replace 'seamless' — what specifically do you mean?",

"Replace 'delve' — what specifically do you mean?",

"'It's not just a tool. It's' — setup-and-resolution is a rhetorical tic. Just state the point directly."

]

}The score is useful for triage. Above 80, ship it. Between 60 and 79, worth a second look. Below 60, revise before anyone else sees it. Each violation comes with the matched text, surrounding context, a penalty, and a concrete suggestion for fixing it.

The full source is available at eric-tramel/slop-guard. It’s a single file, runnable as an MCP server with uv run slop_guard.py. The benchmark script used for the newspaper corpus analysis above is included in the repo.

What’s Next

The scoring function has properties that make it interesting beyond a linter. It’s deterministic (same input, same output), produces a continuous 0-100 score with good dynamic range from varied to formulaic prose, and the current Python implementation is fast enough for agent-in-the-loop use. For high-throughput settings like RL training, the regex-heavy scoring would likely need a compiled implementation, but the interface and scoring model would carry over directly.

The idea: use the slop score as one component of a reward during RL training to push models toward less formulaic output. Not as the sole objective (that would teach the model to produce very short text that scores 100), but paired with task completion. The rule-based nature is an advantage for this. Unlike an LLM judge, the model can’t learn to game the scorer by learning its preferences. It can only improve by actually avoiding the patterns.

There’s existing work in this direction. @myainotez pointed me to PrimeIntellect’s community environments include an antislop environment built from similar word lists. But it uses coarse integer scoring (0-15 in 3-point buckets) with no density normalization and no concentration awareness. The continuous exponential scoring and the concentration multiplier produce a richer gradient signal for training.

Whether rule-based scoring is sufficient for RL, or whether models will learn to avoid the specific regex patterns while finding new ones not in the ruleset, is an open question. The rules are fully inspectable, which is either a feature (no black-box reward hacking) or a limitation (the model can in principle learn the exact boundaries). Both are probably true. But as a starting point for steering model output toward better prose, a single file of regex is hard to beat.

Feedback

This post was written with an AI agent and checked by the tool it describes. If the writing felt formulaic in places, that’s exactly the kind of signal I want to hear about. Reach out on X or open an issue on the repo with what felt off. Every pattern someone notices that the linter missed is a new rule waiting to be written.